a short oral history of us

Thanks to my family, for sharing their stories, and to my parents, for everything

I’ve thought a lot about cultural identity over the last year, thanks to two things: a rereading of The Joy Luck Club and a Hispanic Heritage Month event at my agency.

The Joy Luck Club follows four Chinese immigrant women in San Francisco and their Chinese-American daughters, as they navigate the trials of building a life in America and the challenges of translating life lessons amidst contextual differences and a generational gap. Told through short stories, the book is a narrative of past and present, of cultural traditions and hope for the future; it explores interwoven themes of love, loss, family, identity, joy, and hope.

Last year, my office hosted a screening of United Shades of America, a series hosted by comedian W. Kamau Bell that delves into America’s many subcultures. We watched an episode called “Latino, USA,” which documented the lives of Latinx immigrants in East LA. It followed a girl who was the first in her family to attend college, a group of Chicano musicians trying to keep the musical tradition alive, and a mother attending night school English classes to better communicate with her son’s teachers. I was fascinated by the emergence of similar themes, and that the sense of pride in their heritage and their dreams for the next generation informed their lives in America and gave them purpose.

I recently read Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates, in which he examined how he as a Black male in America was shaped by the struggles of his ancestors, and how much of the way you understand your place in the world is contingent upon your connection to your roots. It made realize that I didn’t know where my family came from or how we got here, and more importantly, I’d never asked. I write a lot about my personal thoughts and feelings on this blog, but I’m also fully aware that those thoughts and feelings are merely a product of the life and cultural legacy into which I was born. Sometimes I wonder what my life would be like if I were born at a different time, in a different place, into a different family. I wonder who I’d be.

So rather than tell you my story, I thought I’d let my family share it as they know it, in their own words. Facilitating was an interesting task, as I’m not accustomed to being objective about my own life. You have to ask good questions with which to frame the narrative, without putting words into peoples’ mouths. I read a lot of oral histories to prepare, from Frasier and the hashtag to Anthony Bourdain and Get Out.

So here it is, a short oral history of how we came to be.

PROLOGUE: THE BEGINNING

Our story begins in two places—in 1950s Hong Kong and pre-Great Depression New Jersey.

Ye Ye (paternal grandfather): We moved in 1947 from China [Canton, now known as Guangzhou] to Hong Kong. My mother stayed in China until she died. My father go to Hong Kong. Hong Kong was better. The eating, everything is better. Also the education is good.

I just worked in the dockyard as a construction worker. I go to dockyard apply to job, I apprentice under five years. After five years I have experience, I find out to more better job. When I come here, I try to ask some people to hire me, to have job. They say, “I don’t know your experience,” so I show them this [the work permit he still carries in his wallet to this day]. This under training five years. Same here. Otherwise, nobody hire you.

Nai Nai (paternal grandmother): My parents were farmers, moved to Hong Kong. Moved when I was 13 years old.

Ye Ye: We met in Hong Kong.

Nai Nai: 1955.

Ye Ye: Nai Nai was working in a factory. I was working in the shipyard, at the docks, working to build a big ship. Some friends introduced me. They know her. Her memory is much better than me [laughs].

They were married after three years, in 1958.

Ye Ye: 1961, Howard was born in Brunei. [We] moved there to do construction. They used to be the houses, the small one-family houses in Brunei.

Nai Nai: Irene [my dad’s sister] was born in 1962.

Ye Ye: We moved to the USA in 1968.

My mom’s side of the family has been in the U.S. since the 1920s, when my great-grandmother, Pon Shee Chin, arrived from China, a 30-day journey via Seattle to join her husband (completely coincidentally named Pon Chin) in New York. My grandpa is the youngest of three children, born in Hackensack, New Jersey in the back of my great-grandparents’ laundry, Chin Wing Laundry. He was born “Etwood Chin,” a story we all like to tell, because his mother could not pronounce “Edward.” The nurse wrote it down as she heard it.

Grandpa (maternal grandfather): We used to live in the laundry, on 27 Mercer Street. I was born in the laundry. My sister Lil claims she remembers the doctor putting me in a suitcase-like thing, like the thing you put cats in, and taking me to the hospital. Growing up as the only Chinese at school was difficult. My parents didn’t speak English. One of the rich kids in grammar school, the teacher would say [to him], “Oh, I met your mom last night at the PTA,” and I would think, That’s never going to happen for me.

Some nice people [in the neighborhood] said to my mother and father, “Hey, is it okay if we take your kids to church?” The church was right around the corner. We went there for many years ... but I never was baptized because I never believed in it. They used to tell me, “If you don’t believe in God, you’ll go to Hell.” But I used to think, My mother and father don’t believe in God, and they’re not going to Hell. So after I figured that out, I thought, This isn’t right. Lew Azaroff, my Jewish friend who lived around the corner from me, he went to church with me. His mother and father didn’t complain, but he told his grandmother once, and then that was the end of it [laughs].

[The bowling alley] was in the neighborhood. When I was setting up pins, I was in seventh grade. You sit in the middle of the lanes, on the wooden partition. And they’re bowling real fast; sometimes you’re setting up the pins manually, and you can hear the balls rolling down the alley, and you had to jump up on the seat ... [Each game was] ten lines, a nickel a game, and then the bowler would give me a 5¢ tip. I think that I could buy a ice cream popsicle for 5¢ or 10¢ depending upon the size. Comic books were 10¢.

Starting in seventh grade, I had to start working in the laundry after school. In junior high, Lew Azaroff used to organize football games, the whites against the Blacks. I was on the whites. The first year, I decided to go out for football, just for the heck of it. I quit after a while ... because I had to work in the laundry. By that time, I had to work there every day. A lot of kids had to walk past the laundry to get to the bus stop. It was the only high school in the area, so people in other towns would send their kids to our high school. Paramus had no high school, and they’d have to take the bus to Hackensack. A lot of kids in my high school would see me working in the laundry. It was kind of awkward that everyone else had time off and I had to be working.

I didn’t really get much guidance from my parents about school. My two sisters didn’t go to college. I don’t think I spoke to my kids about school. I didn’t know anybody that went to college, especially Chinese people. In the laundry, I met a Chinese engineer from Bendix Aviation. He was sent over by China to learn about this landing system. He inspired me to be an engineer, because he was the first one I’d met.

Mom: You were hands-off. We just knew you expected us to do well. They never taught us life lessons or anything; it was just by observation. You learn by example. You just had to go to school, had to do well.

Grandpa: I think the kids in Chinatown had an advantage over me, because they had programs for kids on how to get into college and things like that. What made you go to college?

Dad: I thought it was the natural thing to do to get ahead.

Grandpa: When I went to school, it was hard [for Chinese people] to get a job. The only way you could get a job was by being an engineer, because you don’t have to interface with people. All my friends became engineers. And white people don’t like math, so it was perfect [laughs]. I met this one guy who was an accountant and I said, “Wow, that’s amazing you’re an accountant.” And after that, people started going into advertising. Like Jim Wong [another relative]; he was an artist. He did the covers for the record albums.

We used to work in the laundry—one customer was a Marine. He had spent some time in China, so he used to come and talk to my father about China. He says to me ... “You know what? One day, you’re going to have a sign that says ‘Chin Wing Laundry and Son.’” So that was supposed to be a compliment. That I was going to be the one with the laundry.

It’s only recently now that I’ve been thinking about discrimination, like against the Blacks. I didn’t really notice when I was a kid. When I was young, the local theater had a balcony, and the Blacks had to sit in the balcony. Me and my white friends would sit in the orchestra. But we were discriminated against too. They used to make fun of us; they used to say “ching chong” and things like that. The guys at the bowling alley would call me “Charlie Chan.” My father used to take us to Palisades Amusement Park a couple of times a year, opposite 125th Street in Manhattan. There was a big roller coaster and everything. They had the world’s largest saltwater pool. The Chinese were not allowed to go in there. To this day, I don’t know how to swim.

PART I: DAD

My parents’ admittedly unconventional relationship can be attributed to a great deal of luck and an even greater amount of patience. For starters, they had vastly different upbringings. My dad is an immigrant from Borneo, an island controlled by three different political entities—Indonesia, Malaysia, and the sultancy of its capital, Brunei.

Dad: Borneo is an island, right on the equator. It was always hot there, so the schools were open-air, with no walls and thatched roofs. It might have been a private school, because everybody dressed alike—shorts and white shirts. And everything was built on pillars, because of monsoon season. There’s this fruit, the durian, that’s very common in Borneo. I used to eat that a lot. I went to first grade there, all the schools were in English. But then we moved to the U.S. [specifically, to Chinatown in Manhattan] and I did first grade again.

Nai Nai: 14 years we stayed in Brooklyn.

Ye Ye: We live in Chinatown almost six years, then move to Brooklyn, then stay there for 14 years, then lived here [in Chinatown] until right now. We live near Brooklyn Bridge maybe 28 years. I do the same job, the construction. No change. Nai Nai was a seamstress.

Dad: My Uncle Ken sponsored us; he was a founding member of Chinatown Federal Savings Bank. Our first apartment was his office—he used to have a real estate business, and we lived out of his office until we found our own apartment. My dad was a painting contractor; he used to paint apartment buildings. He would come home splattered in paint. And my mom was a seamstress. They were paid by the piece, like 3¢ per garment.

Mom: A sweatshop.

Dad: It was like a sweatshop. The faster you sewed, the more money you made.

The New York Chinatown of today looks like an echo of its former self—the colorful, glowing storefront signs remain, as do the Chinese bakeries, the fruit vendor carts, the “WELCOME TO CHINATOWN” sign strung in lights, and the ubiquitous red paper lanterns. Now, it’s a popular spot for hip new eateries and artisan markets, but back then, Chinatown’s appeal to immigrants from Taiwan and Hong Kong made it a thriving center for gang activity.

Dad: There were a lot of Chinese gangs. One of the two main ones was called “Ghost Shadow” and I don’t remember the other one.

Mom: The Bloods and the Crips!

Dad: That’s LA.

Mom: I know, but that’s all I know.

Dad: They’d try to recruit you. They would come up and talk to you and say, “We’d like to get together with you.” I said no. But my sister used to be involved with the gangs. There was a lot of tensions between the Italian gangs and the Chinese gangs, and that’s when we moved to Brooklyn. I’d commute every day to Stuyvestant [a now-prestigious high school in lower Manhattan]. Uncle Davies [his best man] and I used to play basketball together; he lived in Brooklyn too.

Mom: I didn’t know that. I thought you knew him from Columbia.

Dad: No, we go way back. One of the reasons I thought I could go to Columbia was that it was close. My mom cried when I left for college. I went home every weekend.

Mom: Aiyah.

Dad: There was another guy in college named David So. He was the president of the Chinese Student Club, and he asked if I wanted to run the Asian Student Union. We used to run the parties on campus. We had a budget—the school gave us money to throw parties because it was a “student activity.” The Asian Student Union did “Asia Night” to try to encompass all the Asian groups. There were some cultural performances, like ribbon dances.

Mom: You guys should’ve hired me.

PART II: MOM

My mom is a second-generation Chinese-American, born and raised in the sleepy suburbs of Teaneck, New Jersey as the eldest of four children and the only girl. She had three younger brothers—Glenn, Jeff, and David. Growing up in the height of the ‘60s, she spent much of her childhood playing freely outdoors, sledding down their snow-covered front lawn in the winter or swinging on the tire swing her dad built in the backyard in the summer.

Mom: I had a very happy childhood. We didn’t have a lot of money growing up, but we bought [a beach house] ... at the Jersey Shore. Those were my favorite memories, because that was my life. School was just a big blur, but we would spend every weekend in the spring and fall there, and then from the end of June until Labor Day weekend, we would live there all summer. Grandpa would drive down and stay from Friday night to Monday night.

Grandpa: Sunday night. We would start grocery shopping on Thursday.

Uncle Glenn (my mom’s first younger brother): I remember being at the beach, hanging out with my friends, riding bikes, riding my moped. I always wanted to make money because I wanted to buy bikes and mopeds, so my first job at 14, I worked as a dishwasher. I looked at the want ads in the paper, and they said, “Okay, come in tomorrow.” I made $2.35 an hour. That was minimum wage. I was always picking out bikes off the street that people would throw out, and I’d fix them. I once bought a bike from a flea market for $5 and fixed it up.

Mom: So he’s had this love of bikes since then.

Uncle Jeff (my mom’s second younger brother): We all worked at the China Pearl. Glenn used to ride his moped and I would ride on the back if we had the same shift. He was a waiter and I was a busboy and a dishwasher. I’d clear the plates; if there was any good food on it, I’d eat it.

Uncle Dave (my mom’s youngest brother): They used to save the old rice and make fried rice the next day.

Uncle Jeff: Yeah, that’s why I tell my kids not to eat fried rice.

Uncle Glenn: It was always three boys and your mom, so she just ignored us because we were always playing or fighting. Uncle Jeff and I used to fight a lot because we were very different, and also because it was just something to do.

Uncle Jeff: We fought about everything.

Mom: I remember them fighting all the time, someone was always on top of someone, someone was always chasing someone.

Uncle Dave: I used to chase the brothers around the house with a stick ... We couldn’t afford haircuts and apparently my mom gave me the worst haircut and I had no hair, so they called me ”Kojak” ... they used to give me lollipops, because Kojak used to suck lollipops. Then they’d call me “Milton the Monster” because I’d get really mad.

Uncle Jeff: Because it bothered him.

Mom: They’d call him “Kojak” and he would flip his stack.

Uncle Jeff: I still remember the [Milton the Monster theme] song to this day [starts singing], “He lifted his lid and blows his stack, he says ‘bye-bye, next week I’ll be back.’”

Uncle Dave: I had no form of retribution or revenge, so instead I had this stick.

Mom: My mom used to chase Uncle Glenn around the outside of the house with a belt, a hanger, or the Board of Education. It was a literal [wooden] board that said “Board of Education.”

Uncle Dave: Can you imagine them selling those at The Sharper Image nowadays?

Uncle Jeff: Just don’t do dumb stuff in front of your parents! I used to go [to the racetrack] every weekend. Your mom went once.

Mom: I did? What did I do?

Uncle Jeff: I don’t know, you probably told Mom, like a dummy. Your mom’s friends were like goody two-shoes, so that was like horrible for them.

Mom: I played with a lot of Barbie dolls. I used to make Uncle Glenn play with me—he used to bring his G.I. Joe dolls and the Barbies and the G.I. Joes would play together. I don’t think I had a Ken, but I had Barbie, I had Skipper. And when I got older, I had these...coincidentally, they were called “Dawn dolls.” They were like miniature Barbies, probably nine inches tall. I had a whole collection of them. They were tiny; everything about them was tiny. There was Dawn and Angie, and I don’t remember the rest. The other thing I remember playing with was this wooden dollhouse set. I played with it all the time. My dad built me this wooden box where I could store all the furniture, and then you open the box and you could rearrange all the furniture. It was so simple, no details. Like just a chair, carved in the shape of that. So I saved it for you guys thinking, Oh, you guys are going to love it. But you guys were never interested because you guys had better plastic furniture with details and accessories. I just had this house with probably ten pieces of furniture in a wooden box. I still have it here; I can’t bear to throw it away because it’s 40 years old.

We had this little metal fire engine, and I think it could seat two people. When the weather was nice, we’d bring it to the top of the hill, and we’d go down the hill on that. My dad bought an ice rink for the backyard—it was like a metal frame with a plastic bottom, and we filled it with the hose and we tried to ice skate in the backyard. I remember it not being successful, but I do remember trying that. It was all dangerous; everything I did was dangerous, and my mom was never watching us.

Grandpa: Remember we used to go sleigh riding down the hill?

Mom: Yeah, we’d sled down the hill and you’d just keep going.

Uncle Jeff: We had a steep hill and it went [around a corner] and if a car came—

Mom: You could go under the car.

Uncle Jeff: I just remember our youth was just athletics and going to the beach. All summer, we’d wake up in the morning, we’d see how the waves were, and if they were good, we’d stay at the beach like four hours a day. We’d boogie board or body surf.

Grandpa: We’d just go down to the shore since ‘72 or ‘73.

Uncle Dave: We’d go to the beach every day.

Mom: When we went to [a funeral] last year near Atlantic City, I wanted my dad to go [back to Long Beach Island], because he wasn’t going to go back. So we went there, me and all my brothers, and bought these subs we used to buy all the time. On the way back to New York, I said, “I really want to stop at Long Beach Island,” so we drove up and down the island. We bought refrigerator magnets and t-shirts and baseball caps from CVS that we’ll never wear again. We were so happy, buying all of this ridiculous stuff, because it reminded us of when we were little.

Uncle Glenn: The Shore wasn’t all fun all the time. Sometimes I resented it because we went down every weekend, which meant less time to hang out with friends. We went down to work. [Dawn] never cleaned houses because she always worked in the store—I cleaned the apartments in between tenants.

Mom: I was 11 and 12 cleaning apartments; Uncle Glenn was like eight, so he probably doesn’t remember.

Uncle Glenn: After I got my outside job, she worked at A&W. I worked either as a dishwasher, or I had a commercial clammer’s license. I was a busboy, a waiter, I worked at a carpet store.

Grandpa: We used to go clamming and we would sell them for 10¢ a clam. We had a sailboat—Sunfish—and a 16-foot Bayliner that was also good for water skiing.

Uncle Jeff: We had a commercial license so we could sell them to fishermen. That was so much work. It was like 200 clams in three hours, so it was six bucks an hour. We used to go to this Long Beach Island surf shop, so we would go in all the time and think about what we would buy. [At the restaurant] we made $2 an hour in wages, and then we made tips. So I’d come home with like $50 a night. We’d just buy surf-related stuff. Skateboards, t-shirts. It was a good life, no complaints.

Grandpa: I used to keep $20 in the glove compartment of the Bayliner, so you could get gas, but nobody ever used it. Actually, when we were growing up, I used to put $20 under the sink. It was the honor system, but no one ever used anything.

I’ve never met my real grandma, but I’ve always known two things about her: that I’m named for her, and that she died when my mom was only 21 years old. The rest I’ve had to put together from what other people have told me. She was an amazing cook that loved company, and would often spontaneously invite people over for dinner. She also loved projects—she had a little Chinese food shop at the Jersey Shore, which later became a trinket shop.

Grandpa: [How we met] is a long story. Going through high school, we never had girlfriends. My mother wouldn’t let me date white people. And my friends weren’t interested in girls either. Nobody went to dances or anything. When I was young, going to college was...no one ever thinks of that. I decided after high school, I said, “Maybe I’ll go to an electronics school.” It was called RCA Institute. I went there for two years. And then after that I started working, and the first job I got [was a technician]. All the engineers were in cubicles and the technicians sit on the bench. You work with tools, build circuit boards. And I was on the bench! I thought, This is no good; I’d better go back to school. So I went to Fairleigh Dickinson University.

They teach you electronics and math, [but] they don’t teach you things like English or history or economics. So when I was working, I took some English literature courses, and then I decided to go to Brooklyn Polytech [Brooklyn Collegiate and Polytechnic Institute, now part of the NYU Tandon School of Engineering] night school every Monday, Wednesday, Friday, because I worked full-time during the day. I was a junior engineer at that time. We had class from 6 to 10 pm. I’d get home around 11, three nights a week. That was killer. I did that for about four or five years.

When I went to Brooklyn Polytech, I’d stop in Chinatown to get something to eat, get some noodles or something. I met my cousin there and he said, “Hey, I’m going to church, singing in the choir, why don’t you come with me?” So I got to know the people in the choir—my first Chinese friends. They had a social club in Chinatown called The Four Seas. At Christmastime, they used to visit the hospitals in New York and give presents to the Chinese patients. There was a girls’ club called Ging Hawk Club [scrapbook from MOCA here]; a lot of girls from Hunter [College] or CCNY were in that club. So we went to the hospital and the Ging Hawk girls came too. After we finished the hospital, we went to Chinatown to have a snack. I was there, Jenny was there, and her sister Anna was there.

Every New Year’s they had a big dance at a hotel. In those days, we used to go to these fancy dances where the girls got all dressed up. The biggest dance was on New Year’s Eve ... I guess it was fun because you knew most of the people there. The Tom sisters and my sisters all went to the New Year’s dance. So Anna said, “My sister doesn’t have a date, do you want to ask her to go?” I was in my late 20s. I had a late start. She was very lively. She was popular. Everybody liked her.

Mom: My mom was such a good cook. My dad worked in Connecticut and he’d leave work at 4 pm ... at 5 o’clock when my dad would come home, you could smell my mom’s cooking outside. She was so impressive; every night, she cooked a big meal. Probably half the time, it was Chinese food. She’d make her own fried chicken in a wok. I remember her making beef with broccoli, steak, pork chops, lamb chops. [She] would marinate pieces of pork in cha siu sauce and hang them from paperclips in our oven, so our oven was always a mess. I just remember rice and some vegetable. Of all the sisters, she was always known as the cook.

Grandpa: She used to teach Chinese cooking classes in Teaneck High School in the evening. It was a lot of work.

Mom: I have all her recipes. They’re all hand-written. But when Uncle Dave was a baby, my mom was a stay-at-home mom. She wanted to open a business, so she started this little Chinese takeout place; it was literally just a counter and we had a very limited menu: shrimp and chicken chow mein, egg rolls, wonton soup, cha siu bao. I used to fry the egg rolls, take money at the register, and count the change in my head, because we didn’t have calculators. [My mom] went to auctions and bought all this stuff from restaurants that were closing down, and my dad would have to haul it into our station wagon.

Uncle Glenn: We had parakeets once, and they need to be covered at night. One night we forgot, and the next morning they were sitting on the ground dead, because they got cold. Grandma Jenny used to hang wash outside. It was a nice day, so she was outside hanging laundry. We had another parakeet—the birdcage was open and the bird flew out, so we went to the store and got a replica, and Uncle Dave totally knew. The bird’s name was Willy, Wilhelmina. We tried to replace it, but he knew.

Uncle Dave: He’s almost correct. We had Willy for a long time, like eight years. And then we got Teddy [a dog], and obviously Teddy ruled the world, so we had to get rid of Willy because Teddy would chase Willy around the house. So we gave him to Aunt Lillian and she had him for a week, then she put him next to the AC and he froze. Willy was the one that was frozen, Charlie 1 was the one that flew out of the window. Then my mother went to Two Guys; it was like a Target—

Uncle Jeff: Like a KMart.

Uncle Dave: But you could tell it was a different bird because [Charlie 2] was missing toes. They didn’t even try.

Uncle Jeff: I picked him out. We felt bad for the bird. No one else would take him.

Mom: My mom was very get-up-and-go. Like, “I think I’m going to do this.” Very spontaneous. One night she’d say, “Let’s go into New York and go to Radio City,” and she’d throw us all in the car and we’d go to the Christmas show at Radio City Hall. There was an empty space next door [to the takeout place], so she thought, Why don’t we open a gift shop? So the idea was that you’d get your food and then shop in the gift shop. Both were called The Gold Wok. The restaurant wasn’t very successful and only stayed open for a couple of years, but the gift shop stayed open for I think ten years. That’s why I loved my childhood; it was a fun childhood. We closed the store at 10 pm every night, and sometimes she would say, “Let’s go to Seaside Heights.” She’d pile us all in the car, and we’d drive 40 minutes to the boardwalk—there were games and ice cream. We would stay up until midnight and then go home. We’d come home and do the same thing the next day. That was our life.

My Grandma Jenny died when she was only 46 years old. But there was a small silver lining: I got a step-grandma, the only grandma on my mom’s side I’ve known in my lifetime. She would teach me things like how to fold wontons by hand, and because she actually spoke Mandarin unlike the rest of my family, how to make my stuffed animals sing Chinese folk songs. She became my mom’s stepmother when my mom was 29.

Grandma (maternal step-grandmother): I was at Teaneck babysitting two kids in a family, Middle Eastern family.

Grandpa: They lived next to Lew Azaroff.

Grandma: During the summer, I had graduated community college and was looking to move to four-year college. I took garbage to garage, but the door was tricky and I locked myself out of the house. I went [next door], happened to be Lew Azaroff. I said, “Oh, I’m just babysitting.” The family left phone number to Lew Azaroff to call them. When I walk around the cul-de-sac, and we talk and he said, “Where are you from?” and I said, “China.”

So I move on to four-year college. So before leave my babysitter family ... [the mom] said, “Betty, I like you, can you leave your phone number so when I need a babysitter I can call you?” But then she call me and said she found another babysitter. She said, “Do you have a boyfriend or friends?” I said I just started school, I need to concentrate. A couple days later, Ed called me. I was so shocked. I didn’t give permission to give my phone number to a stranger. I was by myself, in this country.

Grandpa: Every other week, [Lew and I], we’d take a walk and talk about our [families]. He said, “What are you doing?“ and I said, “Not doing much.” He said, “Oh, I know this Chinese girl,” and that’s how it started.

Grandma: One day he said, “Let’s go out for dinner.” I said, This guy is nice, but what I’m going to do? I thought about it and said, Across the street where I work, there is Japanese restaurant, and in case something happens to me I can run to my boss. But he said, “Where we meet?” [I told him] “Oh, we meet Hackensack bus terminal.” So if something happens I can run, jump on the bus, and go home. After we met, he was fine and we went to the Japanese restaurant. We talked for four hours. We dated for almost five years, because I want to finish my school. It’s not easy for me to go to school, I have English problem. That’s my goal, I want to finish my school. When I finish school, I had a computer science major. The computer department dean was very nice, she said, “Would you like to work? I could get you work permission and you could work for software company.” After I graduated, they kept me and I stayed there for a while. We get married in 1989.

Mom: When I graduated [from Rutger’s University in New Jersey], I worked for Condé Nast. It was just an admin position, and I remember I was only making $13,000 [approximately $36,720 today with inflation]. Then I got a job at Continental Insurance, in financial reporting. And I think I worked there for two years. Then I found the job at Sony ... I started out as a junior accountant, and then I befriended some marketing people and I used to work on some projects with them. I was good at making presentations, which was kind of a big deal back then because we didn’t have PCs. So I learned how to make graphs on a computer; I made presentations for them, and then they hired me in the marketing department. I first worked for the headphone department and then I moved over to car stereos. They called it “Automotive Entertainment,” because they were pretty progressive, and we sold TVs for RVs.

Meanwhile, in New York, just one state over, my dad graduated from Columbia University with a degree in biopsych, because it fulfilled the requirements for medical school.

Dad: You could do like a biochem major, but that was much harder [laughs]. I worked for two years for the Prudential Insurance Company [in a rotational program]—you’re supposed to work two years and then be promoted to associate manager, but I took the MCATs and went to SUNY Buffalo.

In med school, the first two years are basic science, and then the third and fourth you have clinical rotations, where you rotate through things like cardiology, hematology, nephrology. I wanted to work in the ICU—I liked the intensity—so I became a pulmonologist, because a lot of the patients in the ICU are on ventilators and it was the pulmonologists that had to operate.

PART III: BOY MEETS GIRL

My parents meeting was an improbable event—a blind date in my dad’s third and final year of his medical residency post-med school, orchestrated by my dad’s friend Warren at my dad’s insistence.

Mom: [He and Warren] never saw each other, because they were always working. They’d see each other every six months, and he would ask Warren, “Hey, so how about setting me up with your wife’s friends?” and Dad was so annoying that he finally said yes.

Dad: Annoying?!

Mom: He was relentless. But I liked that about him. When he wanted something, he would go and get it. In a nice, subtle way. But he was a man of action. He would just handle things, everything was handled. He was really smart, the smartest guy I ever dated. I used to think I was smarter than everyone, but I finally met someone smarter than me.

Dad: When I met her, right away I thought, I think I want to marry this woman.

Mom: I kept a journal. I wrote something like, “This could be the guy that I marry.”

Dad: I did my residency at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital. When I was a resident, the ER was divided into two parts, Area A and Area B. Area A was the really sick patients, and then Area B was the walk-in clinic. We used to call it “B for Bogus” because they’d say something like, “Oh, I’ve had a headache for ten days” [laughs]. You could moonlight in Area B and get extra hours for extra money.

Mom: That’s how he bought my engagement ring. Because as an intern he made zero money. So it meant a lot because I knew how hard he’d worked to get it. He bought the ring from David So.

Dad: David So’s family was in the diamond business. Didn’t you lose the engagement ring?

Mom: I lost it on vacation in Florida.

Dad: Mom was born at Columbia Presbyterian. When I was dating her and knew I wanted to marry her, I went to medical records and got her footprints that they took when she was born...I framed them and gave them to her when I proposed. In addition to the megacarat diamond ring, how could she refuse?

For those of you that don’t know my dad, the use of the word “megacarat” is his attempt at humor. He proposed to her in her living room.

Mom: Another thing that made me think I could marry him was that I always wanted to move to California. I always thought, I really want to live in California, somehow I’ll make it to California.

Dad: So when I told her I wanted to move to California, she said okay.

Mom: When you’re in your 30s, that’s what you talk about—your future. What your career’s going to look like, where do you want to live, how many kids do you want. We got engaged after four months and married after 17 months. Don’t ever do that, unless you’re 30.

PART IV: WEST COAST STORY

Another improbability—that they both had their hearts set on the West Coast. But my mom refused to go with him unless they were married. So they married at the St. Paul Chapel at Columbia University, my dad’s alma mater, on May 23rd, 1992.

Mom: We had a year to plan it. I didn’t want a traditional Chinese wedding where they just kind of throw the dishes at you and are rude. I got Chinese invitations—that was the compromise—with Chinese on one side and English on the other, and I wore a cheongsam [in Mandarin, it’s called a qipao]. We chose this place called Dish of Salt in Times Square—it was beautiful, but it’s not there anymore.

Dad: Mary Anne Lum, one of the owners, was a very interesting woman. She named the restaurant after a racehorse.

Mom: She had the same kind of vision we had. It was a very interesting Chinese restaurant. Very authentic, because she was from Hong Kong, but it was very sophisticated, nicely decorated, with a loft and two big staircases. Very elegant. We had French service, because I didn’t want it to be a Chinese banquet where it’s just in the middle of the table, like a chicken with the head on it.

We had 186 people, I remember, a lot of friends ... I was the first of my cousins to get married—no one was dating anyone, no one was married, and no one had kids. If I had that wedding now, it would have been a lot more people.

Dad: We were married by a Lutheran pastor.

Mom: The chapel was non-denominational, but I felt like it was such a non-religious thing, so it should be officiated by a religious figure. Back then it wasn’t a thing to be married by a friend. We had a Filipino band.

Dad: It was called “Friends of Mine.” Great band.

Mom: Nai Nai and Ye Ye weren’t happy with the wedding. They wanted a more Chinese wedding. But I wasn’t that kind of Chinese. It was like Crazy Rich Asians, and I’m Rachel Chu. But everyone had a good time because it was the first of its kind: dinner, dancing, party.

Dad: I was blindfolded and I had to eat cherries off a string tied around Mom’s neck.

Mom: Then people had to walk up to Dad while he was blindfolded and kiss him, and he had to guess if it was me—one woman went up to him and kissed him and he was like, “That’s her!” and people went, “That’s not her!”

Dad: Uncle Davies came up with these games.

Mom: Everyone copied our wedding. Uncle Greg and Aunty Cyn used the wedding band. Uncle Glenn had the exact same wedding as I did, at Columbia University, and then at the same restaurant. He even went to Greece.

Uncle Glenn: Yeah, but your mom copied [another relative’s] wedding. Because it was the only cheap, nice Chinese place. Good food, good ambiance. One of our friends who came was so impressed, he said, “Oh, the pageantry of your wedding!” and [someone else] said, “Oh, your stepmother, so elegant!” And we got married at Columbia, because I actually went to Columbia.

Aunty Wai (married to Glenn): We went to New Zealand.

Dad: I’d always wanted to go [to Greece]; I liked the mythology.

Mom: We both liked Greece because neither of us had been. I’d been to Italy and China, and then the Virgin Islands when I was 14, but those were the only times I had been out of the country. We went to the Greek Islands for two weeks for our honeymoon, we came back, and we moved to LA like the next week, just said goodbye and left.

My dad accepted a job at UCLA as a fellow in July of 1992. My mom didn’t want to live in LA; she had her sights set on San Francisco, so as a compromise, they moved to Marina Del Rey, right on the water.

Mom: It was a really unsettling time in LA because of Rodney King. There was a lot of racial tension and the riots had just occurred. The first night we were there, we heard that there was a murder down the street from us, and they found a woman dead in a car a week after we moved in. A woman was dragged in the Target parking lot of the Target I shopped at. I hated it there. I was afraid to go out. I was like, Okay, this is making me very uncomfortable. Everywhere I went, I was nervous, even though it was Marina Del Rey, which is beautiful.

Dad: Mom worked at the jewelry counter in Nordstrom, then got a job at Sony.

Mom: I worked in the Import/Export department for nine months. The people I worked with were very nice, very small group. They made me feel very comfortable. But Dad knew that I was not happy in LA, so he asked his friend to find a job for him in San Francisco. I kept saying, “I don’t want kids right away,” but Uncle Randy was like, “I wouldn’t wait, because things don’t always go as planned.” We listened to him, and then we got pregnant right away. We moved to San Francisco when I was three months pregnant.

PART V: ME

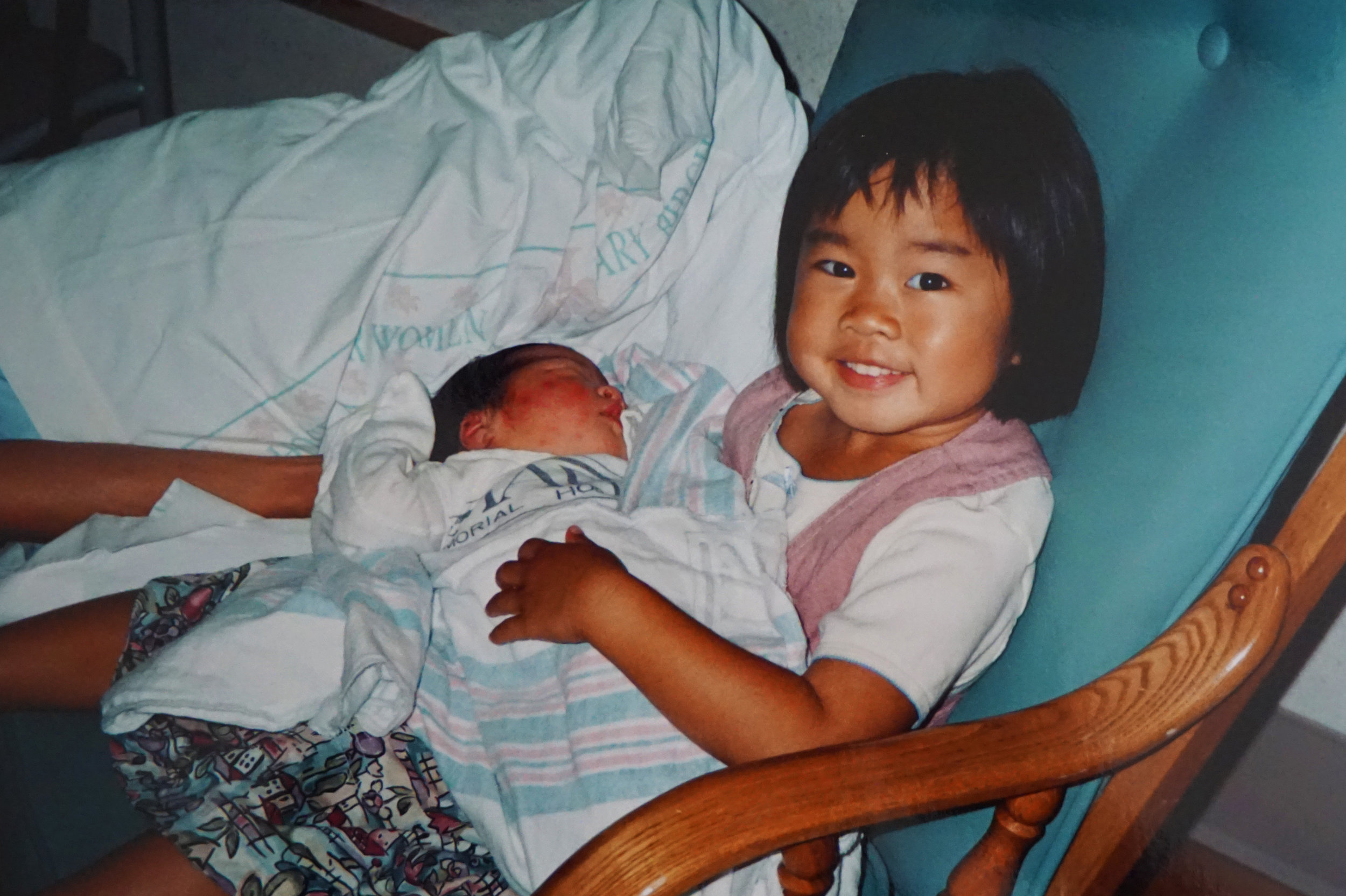

And thus, I was born on December 23rd, 1993 in San Francisco, California.

Mom: Everyone flew out—Grandma and Grandpa, all my brothers were there. Nai Nai and Ye Ye were there. It was like a big party. We had a picture in the apartment; everyone was there, in our small apartment. Everyone was there for Christmas.

We lived in a tiny apartment right next to Japantown in San Francisco. We were so poor from living off of a fellow’s salary that we had to buy really cheap baby clothes [edit: This is the reason that all of my outfits in my first year of life were terrible]. We lived on $32,000 a year [$55,636], in an apartment that cost $1,100 a month [$1,912]. Dad worked really hard because San Francisco was so expensive, that he used to work a second job to supplement his income.

Dad: I was a pulmonary fellow at the SF VA Medical Center. When residents had someone who had a lung problem, you would do an evaluation. There was always someone with a lung problem because everyone smoked—they were veterans, they gave them cigarettes in service.

Mom: He worked at the UCSF VA Hospital and Kaiser.

Dad: I moonlighted at Kaiser, in the ER, because it was very conducive to shift work. You work there for 12 hours and then pass your patient on to the next doctor.

Mom: You had a nanny, who would come in a couple days a week, just to relieve me, because Dad worked all the time. She was Chinese; her name was Lily. She was so Chinese I couldn’t even speak to her. She used to chase you down the hallway—you would run around and she would chase you with a bowl of rice. I used to tell her, “Just sit down! Make her sit down and eat.” There was a little Chinese baby across the hall, his name was Hanson, and his mom used to chase him around the hallway too. It was so funny; you two would run and these two Chinese women would be chasing you guys around with rice.

Dad: SF was nice; I don’t remember much of it.

Mom: We had a great life there—Uncle Randy and Aunty Linda and Aunty Lisa and Uncle Sherman were there. Probably six friends from New York and all their wives moved to San Francisco. Everyone made a big fuss over you, because we were the first of our friends to have a baby. Then Colton came along one month after you, and then Gwendolyn five months after that. Then it was fun, because there were three babies.

We stayed there two years. Dad tried to find a job then, but because San Francisco is such a desirable city, everyone who trains there wants to stay there. Dad was the only one [of his friends] that went into private practice. The closest job we could find was an hour outside of San Francisco and we decided not to take it, so that’s when Dad talked to Uncle Davies, who had [a practice] at Sharp Hospital in San Diego, and they were looking for another doctor.

We moved to San Diego when I was year and a half old. To be honest, I can’t tell if my early memories are ones I’ve remembered, or if they’ve been told to me by family or reconstructed through pictures. But I do remember with clarity specific moments from each of our four houses (we moved several times, all within a two-mile radius—we once moved just two streets over). I remember being terrified of a painting of a man with a green face playing the violin in our Ruette De Mer house. Watching Gymboree on VHS in our Palacio house and requesting that my mom make me PB&J sandwiches, because the characters in the show were singing a song about peanut butter and jelly. Running around the Cloverhurst house playing “Superspies” with my best friend, quietly creeping into the kitchen to hide under the table and eavesdrop on the adults’ conversations, and dissolving into fits of laughter when we were discovered.

Josh (childhood friend, met at 18 months old in a Mommy & Me playgroup): My earliest memory with you, we are probably four years old I would guess, and we are running around your house doing the Chinese New Year dragon under a large blanket.

Gwendolyn (cousin, my age): We used to write letters, hand-written letters to each other, and focus on making our handwriting look “nice” which now looks ridiculous, but we tried. Oh, and we used to have sleepovers in your living room and play steamroller [a game in which we would all zip ourselves inside our sleeping bags and roll over each other], and “Hello Judge.” And one morning your dad woke me up [for school] thinking I was you. We were weird kids. I think we liked having inside jokes. Like, you and me were so attached at the hip, that we liked secrets between us.

Aunty Wai: You were at the bike store with Uncle Glenn and we were there for hours. The woman says, “Oh, your name is Jenny? My name is Jenni, except I spell it with an I.” And Jenny said, “Oh, I spell mine with a J.” You must have been four or five.

PART VI: BOY FORGETS GIRL

Then in 1997, the unthinkable happened. A month before my sister Marisa was born, my dad suffered a stroke when a blood vessel in his brain burst while on vacation in Palm Springs.

Dad: I have a congenital AVM, arteriovenous malformation, so because the blood vessels are malformed and the connections are irregular, the walls of the vessels were weak. I always thought the best thing [would’ve been] if I had been in a car accident and gotten a CAT scan, because they could have seen it.

Mom: He was having headaches a couple of months before, and I thought he was stressed—he was a doctor, so I didn’t think much of it. But he told me later that he was getting his eyes checked and asking the nurses for Motrin. So now I tell all my friends, if you get severe headaches, you should get it checked out.

Dad: [Normally] if you have a headache that’s so severe that you have nausea or vomiting, you take a history, and then you give analgesics like Motrin.

Mom: Do you know why we were in Palm Springs? Because a new baby was coming in June, and two months before, Dad said, “We should go to Hawaii or something, but because you’re seven months pregnant, we should stay here because the medical care in Hawaii may not be as good. Palm Springs is good because we can drive and you can get medical care.”

As we were getting ready to go to the pool, Dad was helping you put on sunscreen and he said, “I have a headache.” He started lying down and said, “I think I’m having a stroke,” and I was like, “What is that.” I thought it was a heart thing.

Dad: I diagnosed myself.

Mom: We called 911, and within 45 minutes he was in surgery. We were right next to the hospital. We stayed at the Renaissance Hotel, because there was a baby pool, and you didn’t know how to swim.

He was rushed to emergency surgery, and was at the Rehabilitation Center at Sharp Memorial Hospital while my mom gave birth next door at Mary Birch Hospital. My mom named the baby Marisa, because it was the only name she could recall my dad liking.

Dad: I don’t think I ever told Mom this. At Columbia, I lived in a coed dorm, and one of the girls in my suite was named Marisa, and that’s why I liked that name [edit: We’d always thought it was for Marisa Tomei].

Mom: Before he went in, the nurses said, “Here’s all his jewelry, and you might want to say goodbye to him.” He was unconscious. I was like, “Okay...bye.” I had no idea what was going on. It was only a couple of days that he was there in the ICU in Palm Springs ... they came in a helicopter and airlifted him to Sharp, because they thought once he was stable, they could take better care of him at Sharp.

Dad: I was in a vegetative state.

It was all a blur to three-year-old me, but apparently our whole network of family and friends helped raise me in the months that followed. I remember my dad’s friend Uncle Davies giving me a little brown stuffed dog that I named Chocolate Chip, that he’d purchased from the hospital gift shop. It was a long road to recovery for my dad—he spent six months in a vegetative state and four months in rehab.

Mom: In a vegetative state, you’re sitting there...you forget how to walk, you had to learn how to eat again, you had to learn how to speak again. He was like a baby. He had speech therapists, occupational therapists, and physical therapists—he had a whole team.

Dad: Speech therapy is more to make sure you don’t aspirate. When you’re recovering in the ICU with a ventilator, you don’t eat, and you’re at a greater risk of food going into the respiratory tract. You’re not sure that the swallowing mechanisms are intact. So that was speech therapy.

Mom: They were working on your memory stuff too. He came out of this vegetative state gradually, in the four months he was in rehab. From morning until dinnertime, he would have therapy. They let him nap, they fed him. He needed it. It took him that long. You, me, and Marisa would go to the hospital and visit him twice a day. It was summer, so they’d wheel him out to the patio. In that time, our whole family came out to visit. All the aunts and uncles would do two-week shifts with us. I was really fortunate that we had a lot of family support, and a lot of people came out and helped me.

Aunty Wai: I remember caring for Marisa when your dad had the stroke. Everyone took care of Marisa because you were easy, but Marisa was a hard baby because she never slept. She was also a hard toddler because at the age of two or three, instead of drinking milk she was drinking lemonade. And Dawn was like, “It’s okay, it’s 10% calcium,” and I was like, “What?!”

Mom: I knew Dad was coming home in November, and people were like, “You need to buy a house,” but we’d never bought a house before. Uncle Steven [Josh’s dad and our family friend] actually came with me and sat in the sales office with me. We said, “Okay, what do you have available?” and the realtor said, “We have this one on Ruette De Mer; you can move in November,” and we said, “Great, we’ll take it.” And that’s how we bought our house.

Almost 22 years later, my dad’s long-term memory before the stroke is remarkably intact—he can diagnose rudimentary ailments based on your symptoms and cite medical research with surprising clarity—but his recent memory, his short-term memory, is limited.

Dad: Short-term is memory that happens in like 30-minute increments. The theory is that everything goes from short-term [to long-term]; it consolidates and forms the long-term memory. It’s like a holding area.

Mom: It was very bad timing; I happened to be pregnant, and he was two months away from making partner. I still can’t believe I was able to survive [my mom’s death] and my husband’s stroke. I had such a carefree childhood, and then when I turned 21, that was the end of all of that. I was Marisa’s age, and then I had to kind of look after everyone and try to start my career. Crazy.

PART VII: MOVING FORWARD

But despite the circumstances, she succeeded. She raised me and my two younger sisters single-handedly, while taking care of my dad. She got into real estate—she would buy houses, remodel and redecorate them, and then flip them. In the process, we moved into our fourth house in ten years: the Greenwillow house. That one was the most fun. We’d swim in the pool from early morning until late at night, until our lungs hurt from holding our breath and our eyes were blurry from diving underwater. We’d play “sock ball” from one side of the staircase to the other, because we weren’t allowed real balls inside the house, tossing a flurry of folded socks at each other until one side claimed victory. We’d have our piano graduation recitals in the “piano room,” with rows and rows of folding chairs spilling into the foyer of our house because all of our relatives and friends couldn’t fit. When I was a junior in high school, Marisa and I made our mom clear out the linen closet in between our two rooms, so we could use it as a shared closet and borrow clothes from each other.

Marisa (my middle sister—loud, effervescent, often refers to herself as “the life of the party” among her friends): Honestly, my earliest memories are mostly in the pool and swimming for like eight hours at a time. Mom bringing out pizza bagels for three meals a day at the poolside. Playing pop-a-grape. And like trading those little beads we had.

Mom: I never let you guys have video games, like Game Boys. When I bought the Wii, it was a big deal because everyone could play it and it gets you up and moving. But I never let you have those handheld ones. We had such a big house that you could run around in and invent games. You grew up without the internet and we watched very little TV, so all you could do was use your imagination.

Me: I know, because Gwendolyn and I used to have a secret clubhouse in my closet with pillows and flashlights and snacks, and we would play Kirby: Nightmare in Dreamland on her Game Boy together. We were very technologically behind.

Kate (my youngest sister—sarcastic, deadpan, also refers to herself as “the life of the party” among her friends): Jenny, did you ever have MySpace?

Me: No, I had Facebook in 2008 but deleted it. I never had AIM.

Kate: I never had a Club Penguin. But I was really into Webkinz. I only logged a couple onto the computer, but I had a huge collection of tags and codes. My favorite one was this little blue hippo that was really ugly as a stuffed animal but was really cute online. I named him Icy. He had a little snow floor. Marisa and I used to play Cash Cow together. There are a bunch of milk bottles on the screen, basically like Bejeweled, and you had to click groups of them to make them disappear.

Gwendolyn: I had Neopets. AIM was life. We had plenty of tech, which is why you loved playing Game Boy.

Kate: I played this computer game with a dog where they would sing about putting jelly on pickles.

Me: That was Someone’s in the Kitchen!. Marisa and I played that, too. And ClueFinders. Remember HitClips? I had a bunch of them all on a keychain, all clipped together, like Britney Spears and Aaron Carter and *NSYNC.

Mom: Yeah, those were expensive.

Kate: By the time yours got to me, there was only three left, and there was one by Destiny’s Child. I would just listen to that one over and over. I also remember having my Tamagotchi at school but we weren’t allowed to take them out during class, so I remember walking across the blacktop after school with my rolly backpack being so sad that it was dead.

Caroline (younger cousin, Kate’s age): You know the Power Wheels, the mini cars that we would drive down the street? Kate had a Barbie Jeep. She insisted I call it “the Jeep” and not “the Barbie Jeep” because she didn’t like Barbie. There are the really short palm trees and they’d always hit me when we were driving up and down the street ... like a year or two years ago, Kate told me, “I used to let you drive on the way there and then switch sides, so you’d get hit by the palm trees.”

Mom: I remember Kate telling me that story and I thought it was so funny. Kate’s always thinking.

Marisa: Remember our cassette player? With the microphone.

Me: Aww, the one where you could like play it back. Remember our pink tent?

Marisa: Of course. We camped.

Me: We used to make blanket forts in the living room too, until Mom made us clean them up. We spent days in there.

Marisa: Hahah. A couple weeks ago, I nannied for some boys who had me build one and it took me back.

Me: Full circle!

Kate: I liked it when we put bags of candy on the inside of the forts so Mom couldn’t see us eating it.

Me: I don’t remember that.

Kate: I distinctly remember gummy peach rings.

Marisa: That was definitely a Kate thing to do.

Me: Where did you even get candy?

Kate: No clue, but I felt so sneaky and smart.

One of my most distinct memories is of being suddenly pulled out of the opening night of my second grade play, the “Three Piggy Opera,” in which I was supposed to play the triangle, and being called to the principal’s office. I was extremely nervous, until my teacher explained that I had to go to the hospital to visit my mom, because my youngest sister had just been born. Marisa, always resistant to change, was not as pleased to have a new baby in the family; in the hospital, when everyone was cooing over a newborn Kate, she loudly instructed everyone in the room, “Quiet! I can’t hear the TV.” She later warmed up to the idea of having a younger sister, mostly because it was like having a living doll. One time when our mom asked us to watch Kate while she was in the shower, we put Kate in a little wooden doll’s bed. We found it hilarious. Our mom, not so much.

Kate: [I remember] crying at preschool. I was standing on a stool and looking through a small window. I remember crying and watching Mom in the parking lot.

Mom: She was hysterical; she wouldn’t stop crying. And the teacher was like, “She’s not really ready,” so I said to myself, I’ll just keep her home with me, she’s my last child. I said, “We’ll try again at three and a half.”

Marisa: Actually, my earliest earlier memories were probably my fourth birthday at Tumbles and being too scared to zipline [but] Jill held me up. I weirdly remember my fourth year of life pretty well. I remember telling Mom, “I’m a big girl now” at age four.

Mom: [Marisa] was so shy; she had a hard time going to preschool, she wouldn’t go sleep over at Grandma’s house by herself. She was so picky, every time we got something new she’d freak out. When we got the Toyota van, she was like, “I don’t like this van, I like the old one!” But then at four, it was like someone flipped a switch, and she was much less shy.

Me: That's actually pretty crazy. I don’t think I remember my fourth birthday.

Kate: My fifth birthday was carnival-themed. I remember we rented a party space and Mom went all out. She bought rolls of paper tickets and you could win prizes by playing games. I had a Costco cake, the one they still make, with white frosting and rainbow balloons on it.

Me: I remember we had carnival-themed things in our house for years afterward. We could use the tickets to buy computer time.

Mom: Or little prizes from my closet, like erasers or stickers. I used to keep a bin of toys and things in my closet. Kate was really into that for a while.

Me: I had a couple of ice-skating birthday parties and I remember I had a chocolate-raspberry Harry Potter cake. I never cared about theme parties, but Mom loves them. When I got older I’d just go and watch a movie with friends, but Mom would still buy little popcorn containers for us.

Mom: I tried to put all these tiny details in them, ones that probably no one cared about but me. I used to match your party favors to the theme of your birthday party. Marisa’s [two] birthday luaus were crazy. We had grass skirts and tiki cups, like who does that?

Marisa: Oh my god, remember your mad scientist party though?

Me: Yeah, remember we painted the garage floor for that and played with dry ice?

Marisa: We did the garage floor all confetti-like and then had that scientist guy come and do experiments. That was very extra.

Mom: I think I parent very similarly to my mom, because I had a very happy childhood, so I tried to create that same environment for you guys. I found I did a lot of things my mom did, except I had money—that was the difference. Just doing fun things. My mom was always doing fun things with us even though we didn’t have money. We went to a lot of shows, a lot of carnivals. I can afford to travel, my mom couldn’t.

When I went to college, people loved my mom. They’d just call her “Jenny”—like, “Oh, she’s so cool, she’s so fun!” To this day, I try to make it fun for you guys. I was so proud that my mom was the cool mom, so I tried to be the cool mom. That’s the way my mom was. We didn’t have parties outside of the house, but she used to make our home parties really fun. I remember she always did things in a big way, so that’s kind of where I got that. Very “extra.”

PART VIII: US AGAINST THE WORLD

As we got older, one of the things we did was travel a lot, something my mom had always wanted to do, because one of the core tenets of her parenting philosophy was that experiences are more valuable than things. She hadn’t traveled a lot when she was younger, with one notable and unusual exception—she and her family lived in the Virgin Islands for a month when she was 14.

Mom: My dad’s company sent him to the Virgin Islands to work; they put him up for a month, so he asked if his family could come. My mom pulled me out of school for a month and had my teachers give me a month’s worth of work. When we got there, they gave us a driver, because it was kind of dangerous there at the time. We lived in a complex, so we met all the other kids. Our mom made us go with the driver to do some cultural things—I think I remember a museum once—but we just wanted to play. We would swim and play hide-and-seek with all the kids at night. That’s why I always pulled you guys out for a little before and after trips, because I thought, Eh, my mom pulled me out for a month.

We took several trips to Mexico when we were little, buying little handheld drums and Chiclets to bring back home with us. Our first international vacation was in 2005, our original cruise to the Baltic Sea, when I was 11, Marisa was eight, and Kate was four. Our mom encouraged us to pick something to collect, to commemorate where we’d been. She suggested thimbles, and thus, a tradition was born, starting in Stockholm, Sweden.

Marisa: [I remember] the dinner at cruises, honestly. I can remember some specific meals I’ve had—the alphabet soup at dinner; I distinctly remember veal ravioli because I didn’t know it was baby cow for a second, pizza at the Lido Deck at night. Oh, and baked beans at breakfast ALWAYS. Oh, and chocolate cake for my birthday, the cylindrical one with the [Princess Cruises] logo on the outside of the chocolate shell.

Kate: Yeah I remember when I was little on that one cruise, the waiter just got me alphabet soup and fruit salad every night without even having to ask me. I forget which cruise, but I remember what the dining room looked like and I remember journaling in my little travel journal.

Me: That was the Baltic Sea.

Marisa: What else...Hawaii, when we went to Fanning Island and called it “Fanny Island.” We got those puka shell necklaces, like way more puka shell necklaces than anyone should ever wear.

Me: I totally forgot about Fanning Island. I remember the water was insanely blue.

Marisa: Yes! Perfectly clear turquoise.

Kate: When was Pompeii? I remember that actually.

Marisa: I remember the Pompeii ruins tragically well, because of the heat.

Me: Pompeii was [the Mediterranean in 2008]. Aunty Sonia got heat stroke and we tried limoncello. It was 104 degrees that day.

Marisa: That day was honestly brutal for everyone. I remember all of us in our dorky sun-protective shirts and hats and pants, and I was so annoyed that I had to wear a sun-protective long-sleeve in 104-degree heat.

Me: That was the first time that it occurred to me that I could actually die from heat.

Marisa: I think I was probably the most dramatic kid I knew, even if it was just mentally in my head, but I think that was definitely a time when I was like, If I wear this long-sleeve shirt one more day, I will die.

Me: And then that awful van ride along the Amalfi Coast.

Marisa: I remember the Amalfi Coast really well; taking the bus around that curvy drive, all packed in the back with no AC. I was so sick, I ran straight to the bathroom in the restaurant. But the food made up for it.

Me: There were 12 of us in one van; it was inhumane. But when we got there, the food was amazing and the view was gorgeous. The pasta with clam sauce was A+.

With each thimble came a story, like the Expo 2010 Shanghai, where each building was a beautiful representation of each country—the puffy pink Japanese pavilion made from recycled materials, the elaborate Saudi Arabia pavilion decorated with living palm trees, the Iran pavilion with tiled fountains inside, the China pavilion constructed in dougong style. The sunset-painted clay thimble from a village in Rhodes, Greece where I got a silver ring that I still wear on my thumb and where we found bits of printed porcelain tumbling among the pebbles in the crystal-clear water. The forest in Helsinki where we drank tea and ate pastries. The hike to the waterfall in Maui. The floating market and river resort in Ayutthaya, Thailand where we celebrated the Thai new year by throwing buckets of water on passing cars with the locals outside of our hotel. The long train ride that we took in Skagway, Alaska where we would stand outside on the decks of the cars with “Flight of the Order of the Phoenix” on repeat on our iPods, pretending we were flying.

Kate: I don’t really remember Hawaii, but I remember Dad’s seizure the night before.

Me: That was in 2006. That’s when Aunty Wai lost our passports, and we would eat chicken tenders from McDonald’s a lot.

Marisa: I remember Dad’s seizure super well. I was in the shower and I came out, and all hell was breaking loose. Grandma was freaking out, all I see was Dad foaming at the mouth downstairs, and I kind of ran back up because I didn’t know where to go. Then the ambulance came.

Kate: Yeah, I remember standing in your room and looking at all the blood on your carpet.

Marisa: Yeah, and all the blood on the walls from his seizure that night.

Dad: When I think about the seizures, I had one in Palacio. When I was walking, I thought I tripped, and I hit my head against the curb. Because all my seizures after that were when I thought I had tripped.

Mom: Amazingly, other than that, he’s actually pretty healthy. Other than all these walking issues, he’s in good health.

EPILOGUE: HOW FAR WE’VE COME

A couple of years ago when I was in Singapore, my mom explained to me over Skype that she felt sad that two of her kids were out of the house and all of her friends with kids my age were traveling and doing things with their husbands. “Don’t be sad!” I told her. “These are your golden years; you’ve accomplished everything you need to and now you can just relax and do things for the sake of doing things! You don’t have to just be a mom anymore. Live your best life.” And since then she’s taken it to heart, focusing on things for herself and her happiness, like learning to play mahjong and Pickleball with new friends.

Mom: What does every mom want for their kids? You want them to be happy with where they are and healthy. To me, happiness is all about connections; it’s not about how much money you have. When you were young, we were still trying to make it. When I married Dad, we had zero money. You guys lived a very privileged life, but that did not come easily. My definition of happiness has changed because I could finally sit back and relax. When you said to me last year “live your best life,” I didn’t take that lightly; I tried to take care of myself. I did stuff only for myself, I worked a little. [Now], Pickleball is something I can do for myself to enjoy for an extended period of time.

I hope that one day you can live your best life and relax, and that you realize that it’s not all about work. Money doesn’t hurt; it makes life that much simpler and much less stressful. But I wouldn’t worry so much about securing your future, like investing at 25. That little money that you’re putting away will not be significant someday down the line when you get married and have kids. I wouldn’t obsess over it and not do things because you don’t have the money.

Uncle Glenn: I think [live your best life] is good advice. That, and “work hard, play hard.” Kind of the same thing.

Mom: I don’t think I really have any regrets. I wish I had lived in New York City, but I did live in San Francisco. I’m happy with my life. With everything that went wrong in my life, I definitely learned from it.

Grandpa: You mean, what are they going to put on the tombstone?

Grandma: “Loved family, loving heart.”

Mom: They always say the same things—“beloved wife, mother, father, son.”

Me: I know, but it’s not actually about what’s on the tombstone! It’s about what you want your legacy to look like.

Mom: I’ve actually thought about that. I try to live my life with my eulogy in mind, so when I die, someone isn’t like, “Oh, she was a great employee at Sony.” Because nobody cares. You want to be remembered as a good mother, that you were generous and kind.

Grandpa: Be proud of your roots. Love yourself and family. Be honest. Respect each other. Help each other. Appreciate what you have.

Grandma: Grandpa, for himself, spend money, he doesn’t buy expensive things. But when family, come family vacations, that’s a lot of money. He is very generous.

Grandpa: That’s how these family vacations started.

Grandma: We said, “We are getting old, we should take the kids see China, let them learn the culture.” But then we come back, Josh said, “Grandma, Grandpa, we had a wonderful time. Where are we going next?”

At the time of writing this, I’m strategist working in advertising in New York City, Marisa is a recent graduate of Chapman University preparing for nursing school, and Kate is a rising senior in high school. To my family: I love you, I’ll dream about you.